Screen-grab from HBO’s Chernobyl miniseries. Source: Youtube/HBO

Article by: KGB Files Edited by: Yuliya RudenkoUkrainian historian Eduard Andryushchenko can’t get his hands off the declassified KGB archives that Ukraine opened up as part of its decommunization initiatives. In his show KGB files, he describes 10 ways that the KGB tried to cover up the disaster that he found in the archives.

At the end of April, we observed the 35th anniversary of the event that has changed the world, and the consequences of which, unfortunately, will be felt for a very long time. It was the Chernobyl disaster.

If you watched the sensational HBO mini-series, you probably remember scenes of KGB surveillance and attempts by this security service to hide the truth about what happened.

Since recent times, declassified documents of the KGB about the Chernobyl nuclear power plant and the 1986 became available. Eduard Andryushchenko, a Ukrainian historian, journalist and creator of the KGB Files history channel has selected interesting excerpts from some of the KGB files found by his colleagues in the archive of the Security Service of Ukraine.

Most of them were published in the compilation “KGB Chernobyl Dossier”, which came out in Kyiv, 2019. The book is free and available in Ukrainian or in Russian via the link.

Eduard Andryushchenko has searched among 200 documents, selected and translated the 10 most instructive excerpts.

The first document is dated late 1978 — it’s more than 7 years before the accident.

The chief security officer of Chernobyl region, Comrade Klochko, informed the head of the KGB directorate of Kyiv and Kyiv oblast, Nikolay Vakulenko, that not everything was going well at the station:

We continue to receive data from agents and proxies, indicating gross violations of technological standards of construction, fire safety and safety engineering of construction and installation works, which lead to accidents.

There are facts when individual leaders deliberately commit gross violations of technological standards for building construction, thinking only about how to hand over facilities quickly without worrying about their future and possible tragic consequences.

The seven pages of this document list specific shortcomings in the construction of new plant facilities. They are full of special terminology that is incomprehensible to a person without a technical background. But in general terms, Klochko, referring to agents, reports about weak building structures, poor waterproofing, low-quality concrete, fires in the main building and machine room, accidents with workers.

And the conclusion is: Poor construction quality, lack of proper control by the Construction Directorate may lead to further destruction of construction sites, radioactive contamination of the environment, and other emergencies.

This memorandum, also from the pre-disaster period, is dedicated to the type of nuclear reactor used in Chernobyl, a reactor that will later become notorious — RBMK-1000.

…information about the insufficient reliability of RBMK-1000 type of reactors used at the Chernobyl nuclear power plant was recieved.

The design flaws of the reactor, as well as individual violations of the rules for its operation, can become the cause of serious accidents.

This reference was drawn up on 29 April 1986 — 3 days after an accident.

During those days there were about 24,000 foreigners in Ukraine, 6,000 of them were in Kyiv. There were students, tourists, engineers, diplomats among them.

They had already heard about Chernobyl but did not have full, accurate, and relevant information. They did not understand how dangerous the disaster was and what they were supposed to do, they were scared and wanted to go home as quickly as possible.

Tourists of the USA group (31 people) … who lived in the Rus Hotel, tried to purchase air tickets to Leningrad for early departure from Kyiv in the morning of April 29, 86, putting pressure on the hotel administration. The measures were taken through the ARO [acting reserve officer] and agents, the situation was normalized, the group went on an excursion.”

The Soviet regime called Western media reports of the scale of the catastrophe a lie and an exaggeration. Foreign journalists who arrived in the Ukrainian capital tried to talk with ordinary passers-by but had great chances to meet the Chekists without a uniform who said only the “right” things.

There are 16 foreign correspondents in Kyiv. Attempts of correspondents from England, France and Sweden to collect biased information at the Kyiv railway station were prevented by bringing in members of the KGB special team from neutral positions that locked foreigners into themselves.

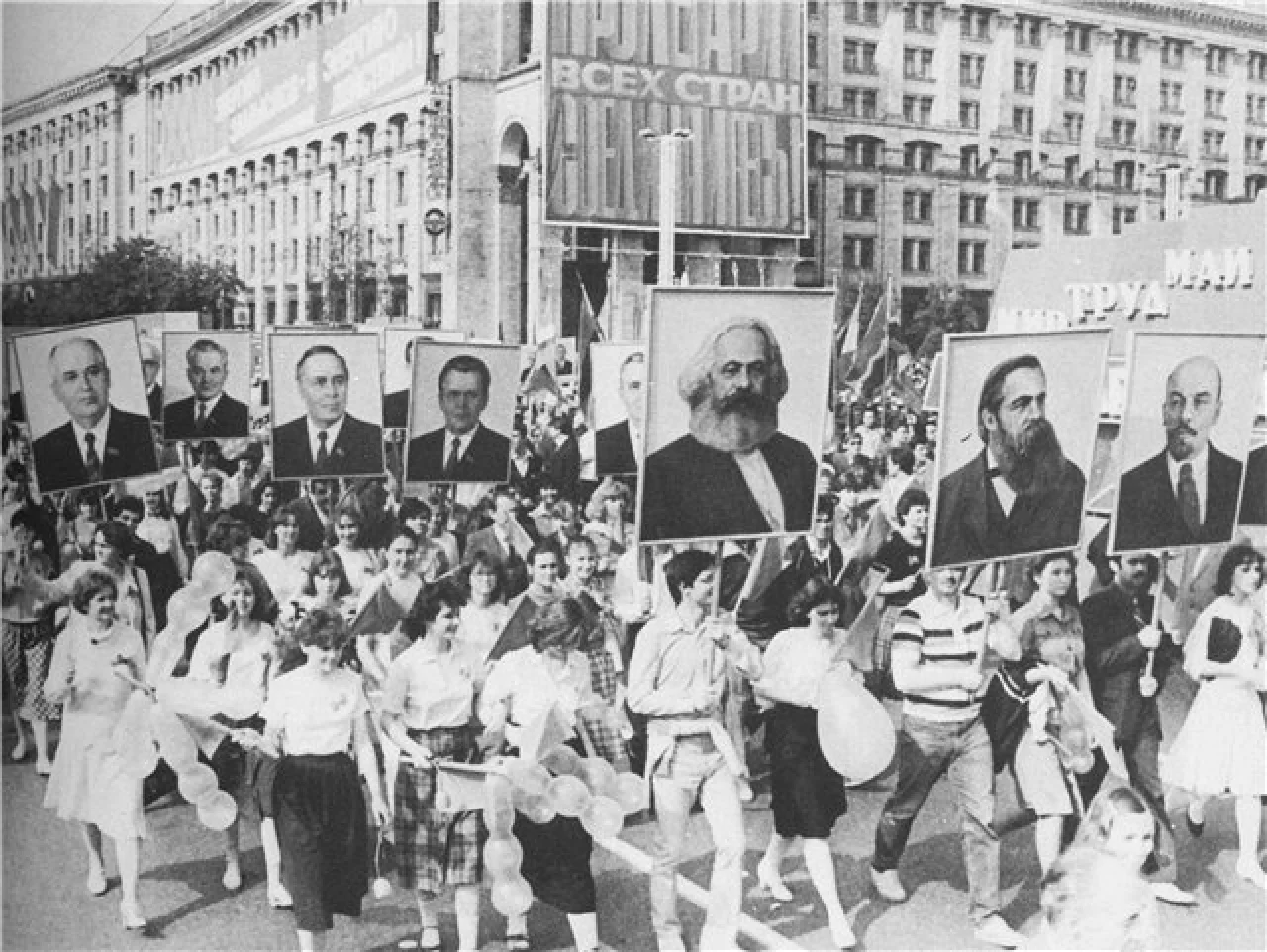

One of the tragic pages of the spring of 1986 is the May Day demonstration in Kyiv.

During these days, it was better not to appear on the streets of Kyiv — or even better to leave the city.

But the authorities decided that the traditional May Day demonstration in the center of the Ukrainian capital should take place in order to avoid panic among people and not to disclose information about the disaster. It is a well-known fact that the head of the republic Volodymyr Shcherbytsky was against the rally, but his Moscow boss Mikhail Gorbachev ordered it to be held at any cost.

Shcherbytsky was forced to obey, and, in addition, personally came to the demo together with his grandchildren. By the way, the scene with the demonstration, transferred from Kyiv to Minsk, was supposed to enter the HBO mini-series but was deleted.

During the preparation of the May 1 demonstration, school students received training suits in which they rehearsed the program on [April] 27, 28, 29. From May 5 to May 8, these costumes were handed over to schools. Clothing has a fairly high level of background radiation. Schools intend to hand over costumes to the palace of pioneers. Decontamination required.

Aspirations of the authorities to maintain secrecy around the disaster at the initial stage even forced doctors to literally lie to their patients.

According to the Shevchenkovsky department of the KGB, the administration of the Kyiv Oblast hospital and 25 [another] hospitals, referring to the instructions of the Ministry of Health of the Ukrainian SSR … indicates a diagnosis of vegetovascular dystonia in the medical records of patients with signs of “radiation sickness.” According to the head physician of the regional hospital, A. Klimenko, such a statement of the question may subsequently lead to confusion when prescribing treatment, diagnosing, and also resolving the issue of disability and establishing a pension.

We have a KGB list of data on the Chernobyl disaster that should have been classified. This list, relevant for the summer of 1986, consists of 26 items.

Among them there are the following:

1. Information disclosing the true causes of the accident at Unit 4 of Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant.

2. Complete information on the nature of the destruction and the extent of damage to equipment and systems of the unit and nuclear power station.

3. Information on the values and composition of the mixture ejected during the accident.

4. A summary of the radiation situation, containing the characteristics of pollution in the premises of the nuclear power plant and in the 30-kilometre zone.

5. Information on the results of individual measurements of the radiation situation and the isotopic composition of soil and water.

9. Information about new effective means and methods of decontamination.

11. Summary of radioactive contamination of natural environments, food and feed in excess of the maximum permissible concentration.

14. Generalized information on the incidence of all forms of radiation sickness of people exposed during the accident and the elimination of its consequences.

16. Information about the results of treatment with new methods or means of radiation sickness.

18. Summary of environmental assessments of the consequences of the accident.

The scene of the mini-series with the soldiers drinking a huge amount of vodka seemed unrealistic and anti-Soviet to some viewers. But what do the KGB documents tell us?

Eduard Andryushchenko found two mentions of vodka in the compilation.

The first concerns not soldiers, but civilians — residents of the Polisky district near Chernobyl.

May 8th at 7 PM a lorry with vodka arrived in the central square of the town [Poliske] and its sale began. A crowd of about 1,000 people formed, a stampede, scandals took place. The lorry was sent outside the city (5 km), which allowed to disperse the crowd and normalize the situation.

A lot of people that haven’t been involved in work, hooligans have accumulated in the city and the district, they take 10-15 bottles of vodka each, increased police work is necessary.

Unfortunately, there is no clarification in the document whose initiative was the sale of vodka.

Another message is devoted to the situation in Ivankivsky district:

On May 9, the vice-chairman of the regional executive committee, Comrade Fursov, banned the sale of vodka, in connection with which on May 10th and 11th groups of military, police officers and evacuated persons (2-3 people each) made scandals in the district consumer union. A police post was put up on the basis of the district consumer union.

It should be noted that this happened during the anti-alcohol campaign of Gorbachev when the sale of alcohol was severely limited.

A huge amount of food that year was contaminated with radiation. And not all of it was seized and disposed of in time — including due to corruption.

…the source [agent] witnessed a conversation between two sellers of vegetables who sold radishes in this market with an increased level of radioactive contamination, having passed dosimetric control for a bribe.

The last document is dated 1988. Interest in Chernobyl throughout the planet did not subside. The communist regime, on the basis of the ideas of perestroika, tried to show that it had become more open, and was no longer trying to hide the truth about the disaster. But, as we see from the KGB files, to a large extent these changes were just an illusion.

In October 1987, the correspondent of the French newspaper “L’Humanité”, Jean-Pierre Vaudon, with tricks, took samples of soil and water in the vicinity of the Shelter object and in the town of Pripyat, as well as along the line in the village of Priborsk (50 km from the Chernobyl nuclear power plant). During the measure “D” [secret search and seizure], samples taken by a foreigner were detected and secretly replaced with radioactivity-free clean samples.

Interestingly,“L’Humanité” was a newspaper of the French Communists, which occupied mainly a pro-Soviet position and received regular subsidies from the USSR.

Eduard Andryushchenko found an article by Vaudon published after his visit to Chernobyl in November 1987. The author notes:

“But I am allowed to take samples of soil, water and branches at the foot of the reactor buried under concrete when, everywhere in the world, it is prohibited to do so close to the power stations.”

It remains unclear why Vaudon writes nothing about the results of analysis of these samples, which, as we know, have been replaced.

You could close this page. Or you could join our community and help us produce more materials like this. We keep our reporting open and accessible to everyone because we believe in the power of free information. This is why our small, cost-effective team depends on the support of readers like you to bring deliver timely news, quality analysis, and on-the-ground reports about Russia's war against Ukraine and Ukraine's struggle to build a democratic society. A little bit goes a long way: for as little as the cost of one cup of coffee a month, you can help build bridges between Ukraine and the rest of the world, plus become a co-creator and vote for topics we should cover next. Become a patron or see other ways to support. Become a Patron!

To suggest a correction or clarification, write to us here

You can also highlight the text and press Ctrl + Enter