Although all five freedoms found in the First Amendment are equally important, freedom of speech remains a cornerstone of any democratic and free society. As activist Deeyah Khan said, “Freedom of speech is a human right and the foundation upon which democracy is built. Any restriction of freedom of speech is a restriction upon democracy.”

According to a recent 2021 survey conducted by the Freedom Forum, freedom of speech is considered to be the “most vital” freedom found in the First Amendment with 59% of respondents citing it as such.

In honor of Free Speech Week 2021, the First Amendment Museum has compiled a list of ten great free speech moments from 20th-century American history.

Note: The free speech moments chronologically listed below were selected by the staff at the First Amendment Museum, but there are many notable free speech moments in our history. What would you consider a great free speech moment of the 20th century? Tell us your picks!

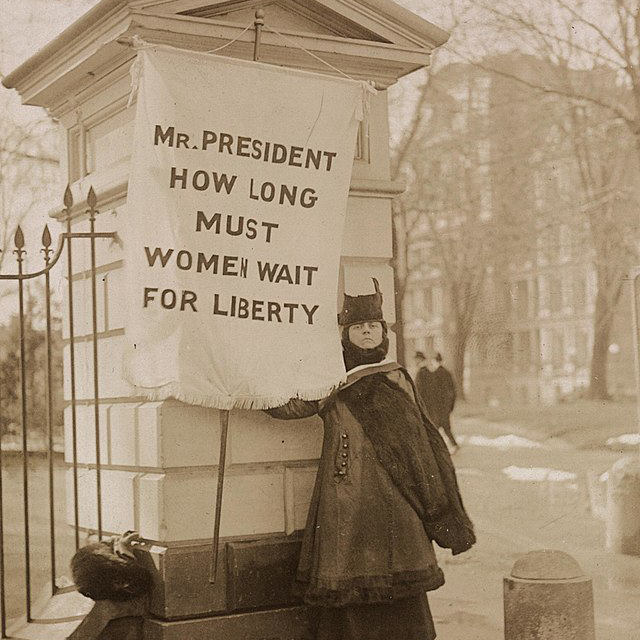

Sometimes, the most powerful speech can involve no words at all. One of the most iconic protests of the Women’s Suffrage Movement was conducted by a group called the “Silent Sentinels” organized by Alice Paul, a Quaker women’s rights activist with a commitment to non-violence and women’s suffrage. The Silent Sentinels protested in front of the White House during Woodrow Wilson’s presidency, from January of 1917 to June of 1919. The protesters wore sashes, held banners, and carried flags with messaging on them in support of women’s right to vote.

The Silent Sentinels used silence instead of loud demonstrations as a form of protest, which was a new strategy within the national suffrage movement. Although the protesters were silent, their presence and messaging amplified the inequality that existed at home while the United States was fighting World War One abroad to make “the world safe for democracy.”

Throughout their two-and-a-half-year-long vigil, one of the longest continuous protests in American history, many of the nearly 2,000 women who picketed suffered from police brutality. In November of 1917, many of the Silent Sentinels were arrested and imprisoned, and further suffered cruelties that included being force-fed, beaten, choked, and abused until they were released weeks later. Over the course of the entire Silent Sentinel protest, nearly 500 women were arrested and 168 served jail time for their steadfast belief in the importance of women’s rights. These protests became one of the most effective in American history and helped spur the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment which granted women the Constitutional right to vote.

The entry of the United States into World War One ushered in an unprecedented era of paranoia in the country. German spies, communist agents, and other “subversive elements” were thought to be pervasive. In 1917, Congress and President Woodrow Wilson passed the Espionage Act which was intended to prohibit interference with military operations or recruitment, to further restrict insubordination in the military, and to prevent the support of enemies of the United States during wartime.

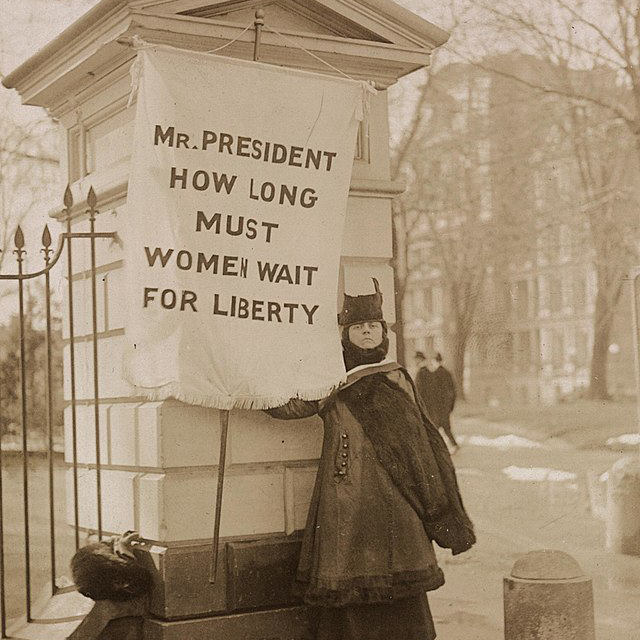

Outspoken members of the Socialist Party, Charles Schenck, and Elizabeth Baer were arrested under the newly imposed restrictions on speech provided by the Espionage Act. They were charged with the distribution of flyers calling on men to “resist the draft,” which they viewed as a form of involuntary servitude. Schenck v. United States went all the way to the Supreme Court. Led by Chief Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., the Court upheld the conviction of Schenck and Baer, and therefore the legality of the Espionage Act itself. The court ruled that Schenck and Baer’s actions represented a “clear and present danger to the enlistment and recruiting service of the U.S. Armed Forces during a state of war.” This case, decided in March of 1919, gave the government a broad license to suppress free speech.

Later that year, in August of 1919, Hyman Rosansky was similarly arrested for throwing fliers off a building in New York City that criticized the US intervention in the Russian Revolution. He and his collaborators were charged under the Espionage Act, and the case, Abrams v. United States also reached the Supreme Court which upheld Rosansky’s conviction—with one notable exception. Unlike in Schenck v. US, this time, Chief Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. dissented, and commented, “the best test of truth is the power of the thought to get itself accepted in the competition of the market, and that truth is the only ground upon which their wishes safely can be carried out.” In this famous dissent, written only months after Schenck v. US, Holmes eloquently laid the groundwork for the “marketplace of ideas” doctrine that has guided much of American jurisprudence on free speech since.

Today, the scientific theory of evolution is a common component of most public high school science curricula, but that was not always the case. In March of 1925 in Tennessee, the Butler Act made it a crime to teach the scientific theory of evolution in public schools. In response, the American Civil Liberties Union asked John Scopes, a high school science teacher, to purposefully violate the Butler Act by admitting to teaching evolution in order to challenge the law in court. Scopes, who had previously substituted for the regular high school biology teacher in the small town of Dayton, agreed and was charged with violating the Butler Act in May of 1925 for teaching evolution from a 1914 textbook.

Both sides lawyered up with star attorneys, and publicity around the trial swelled the public’s interest in the topic nationwide. For the defense, Scopes was represented by Clarence Darrow, a folksy celebrity lawyer. The prosecution was represented by William Jennings Bryan, a prominent Democratic politician who had previously run for president three times. What followed was one of the most memorable court cases in United States history. The lawyers sparred back and forth, culminating in Darrow calling upon Bryan to sit on the witness stand for the defense. Under questioning, Darrow, himself an agnostic, poked at Bryan’s personal Christian beliefs, embarrassing the latter.

Although Bryan’s prosecution performance during the trial was considered lackluster, while Darrow’s was exulted, the jury decided to convict Scopes anyway. However, the highly-publicized trial humiliated the fundamentalists behind the Butler Act in the court of public opinion. By 1927, forty-one bills or resolutions similar to the Butler Act had been introduced into state legislatures. Due partly to the efforts of Scopes, the ACLU, and Clarence Darrow, only two of those bills passed.

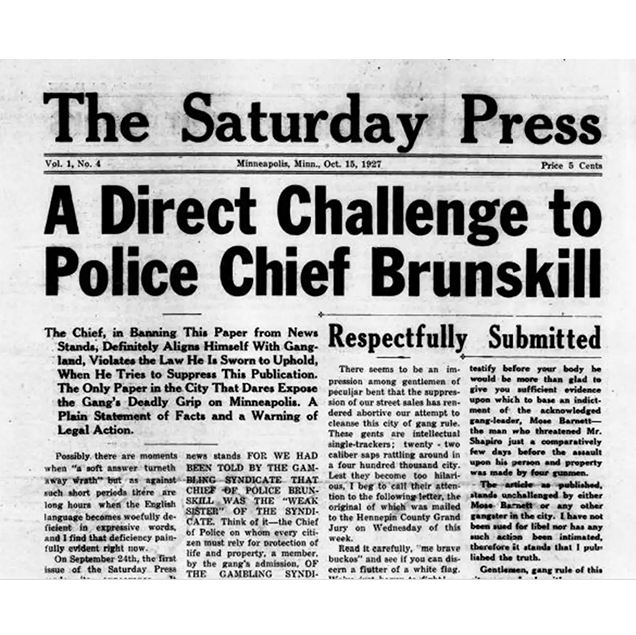

The catch-22 regarding freedom of speech in the United States is that it protects malicious hateful speech just as much as it protects positive or acceptable speech. Near v. Minnesota is an example of this dichotomy. In 1927, Jay M. Near, who was described as “anti-Catholic, anti-Semitic, anti-black, and anti-labor”, published The Saturday Press in Minneapolis, Minnesota. The paper falsely and derogatorily asserted that a Jewish cabal was running the city. Local politician Floyd B. Olson sued the paper under Minnesota’s Public Nuisance Law of 1925 which penalized those who made a “public nuisance” by publishing, selling, or distributing anything considered “malicious, scandalous, and defamatory.”

The case reached the Supreme Court which ruled in Near’s favor, holding that the Public Nuisance Law was unconstitutional since it violated both the Fourteenth and First Amendments. The case violated the First Amendment because it placed an unconstitutional “prior restraint” on the free press. Prior restraint is any law that chills, censors, or silences speech before it is produced. The Public Nuisance Law also violated the Fourteenth Amendment because the Fourteenth Amendment made the First Amendment applicable to state governments as well as the federal. Before the passage of the Fourteenth Amendment in 1868, the First Amendment only applied to the federal government.

Near v. Minnesota was undoubtedly a win for freedom of the press advocates in the United States and has been called the “first great press case” by public intellectual Anthony Lewis. However, the Supreme Court’s decision to allow the paper to spew what we would consider “hate speech” today has muddled the reputation of this landmark decision.

Rosa Parks is now widely known as one of the great icons of the Modern Civil Rights Movement, but in 1955 she was just a young activist standing up against systemic racism. One of the most famous protests in United States history was the Montgomery Bus Boycott which began in December of 1955 and lasted a whole year until December of 1956. Considered a foundational moment in the history of the American Civil Rights Movement of the mid-twentieth century, the boycott began after Parks, a black woman, was arrested for refusing to give up her bus seat to a white person in segregated Montgomery, Alabama.

Numerous events led up to the Montgomery Bus Boycotts. In 1946, the Supreme Court ruled that a Virginia state law enforcing segregation on interstate buses was unconstitutional after hearing a suit brought by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). Then, in 1953, activists in Baton Rouge, Louisiana boycotted the busing system in that city over its racist practices. Two years later, a 15-year-old member of Montgomery’s NAACP Youth Council named Claudette Colvin refused to give up her seat on a bus to a white man. This series of events inspired the NAACP to plant Rosa Parks in a “white’s only” section of a Montgomery public bus in order to spark the boycott. When Parks was arrested for her actions, the boycott began.

Because over 70% of Montgomery’s bus patrons were black, the boycott resulted in drastically reducing the profitability of the busing system. The organization leading the boycott was the Montgomery Improvement Association (MIA) which had just elected as their new president a charismatic preacher named Martin Luther King, Jr. Under his leadership, the boycott continued with astonishing success. Montgomery City Lines lost between 30,000 and 40,000 bus fares each day during the boycott. The boycott garnered national attention and pressured the Supreme Court to declare Montgomery’s policy of segregated busing unconstitutional, ending the boycott. The Montgomery Bus Boycott was an unmitigated success that helped usher in the modern era of Civil Rights, and is a textbook example of using First Amendment rights to shift thinking and policy for the greater good.

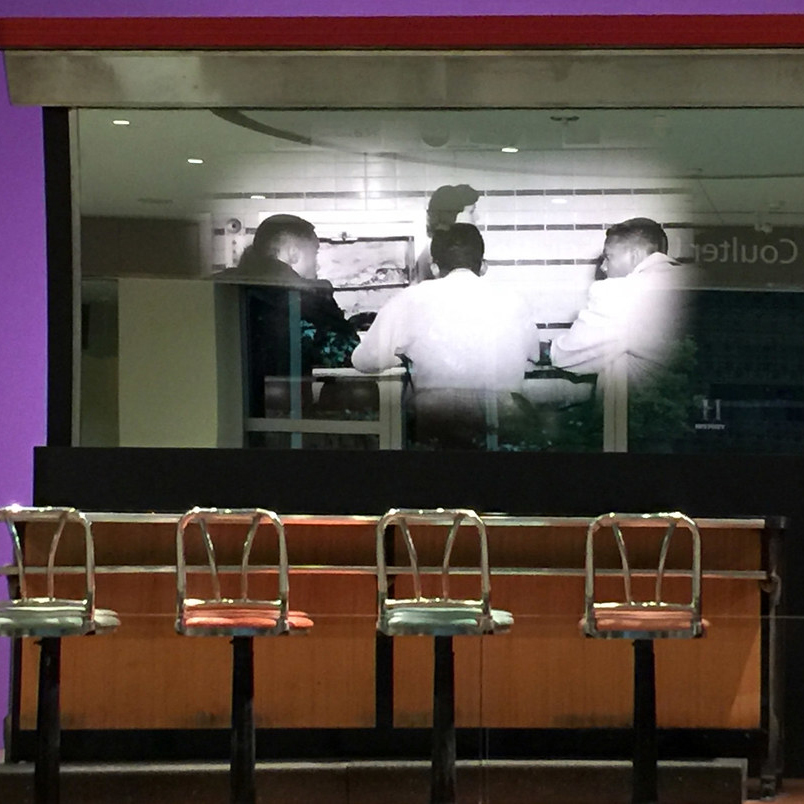

On February 1st, 1960, four freshmen at North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University sat down at the lunch counter inside the F. W. Woolworth Company store in Greensboro, North Carolina. The four had previously been meeting regularly to discuss ways they could personally challenge the racist Jim Crow laws of their community. After sitting down, the men, Ezell Blair Jr., David Richmond, Franklin McCain, and Joseph McNeil, were refused service due to the color of their skin when they each asked for a cup of coffee. After being asked to leave repeatedly, the four refused and stayed until the store closed that night. Then began the Greensboro Sit-Ins. The four returned day after day for almost six months, with more and more publicity, hatred, and supporters following them, until the Greensboro F.W. Woolworth Company agreed to end its policy of racial segregation in July. The last F.W. Woolworth store was desegregated in 1965.

The Greensboro Sit-Ins spawned the subsequent “sit-in movement” in which the events of Greensboro would be repeated across the South until full desegregation of the stores was achieved by the mid-1960s. Over 70,000 people participated in the sit-in movement and many suffered abuse, insult, and disrespect at the hands of angry white mobs and authorities. The Greensboro Sit-Ins also helped catalyze the creation of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) which played an important role in the growing Civil Rights Movement. Today, the International Civil Rights Center & Museum is located in the former F.W. Woolworth store where the Greensboro Sit-Ins occurred.

The March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom remains one of the most famous and important events in all of American history. Perhaps no other event better exemplifies the soul of the First Amendment than the March on Washington. The march was organized by A. Philip Randolph and Bayard Rustin, prominent civil rights leaders who built a diverse coalition of activists for the March under the banner of “jobs and freedom.” It took nearly two years to plan and attracted civil rights groups, labor unions, and religious organizations. The organizers of the March ruled out civil disobedience and insisted the gathering be a peaceful and legal event with cooperation from the Washington D.C. police.

On August 28th, 1963 around 250,000 activists arrived in Washington D.C. to make their voices heard. The March began at the Washington Monument with female participants marching down Independence Avenue, while male participants marched on Pennsylvania Avenue. Both converged and ended at the Lincoln Memorial. There, representatives from each of the March on Washington’s sponsoring organizations addressed the crowd from a podium on the memorial’s steps. The speeches culminated in the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. issuing his famous “I Have a Dream Speech.”

The March is credited with helping to pass the Civil Rights Act of 1964, a landmark bill in Civil Rights history. The media coverage the March attracted gave many Civil Rights groups and leaders national exposure, carrying the organizers’ speeches and messages to a wide audience around the country and the world. Voice of America even translated the speeches and rebroadcast them in 36 languages. The March served as a template for the later Selma to Montgomery marches in 1965. Michael Thelwell, an activist and participant of the March, said, “so it happened that Negro students from the South, some of whom still had unhealed bruises from the electric cattle prods which Southern police used to break up demonstrations, were recorded for the screens of the world portraying ‘American Democracy at Work.’”

During the 1950s, heightened tensions with the Soviet Union ushered in a wave of hysteria regarding fears over the spread of Communism. In response, universities in California enacted numerous regulations limiting students’ political activities. By the mid-1960s, however, encouraged by the Civil Rights Movement and the burgeoning anti-war movement, students at the University of California, Berkeley, began testing the limits of their collegiate free speech. Students began meeting off-campus to hold political demonstrations and rallies, often raucous affairs which sometimes resulted in student arrests. The press took a special interest in the students’ activities and portrayed UC Berkeley as a haven for left-wing radicals. In response, the school’s administration vowed to enforce prohibitions on student speech and political demonstration.

In 1964, five hundred students marched on Berkeley’s administration building to protest the university’s anti-speech rules. The students called for an abolition of all restrictions on free-speech rights throughout the University of California system. In October of that year, former graduate student Jack Weinberg refused to show his identification to the campus police and was arrested. Thousands of students gathered in response and surrounded the police car Weinberg was detained in for the following 32 hours, all while Weinberg was inside it. The car was used as a speaker’s podium until the charges against Weinberg were dropped. Then, on December 2, thousands of students occupied a campus building to force the school administration to relinquish restrictions on political speech and action on campus. After these events, Berkeley’s officials began to relent. By January of 1965, the new acting chancellor, Martin Meyerson, established provisional rules that allowed political activity on the Berkeley campus. The win for free speech was seen by many as a watershed moment for white youth activism during the 1960s. The Berkeley Free Speech Movement not only essentially dismantled free speech restrictions on college campuses in California, but also helped catalyze the anti-war movement amongst young people who could now use their voices safely and legally.

During the summer of 1964, Ku Klux Klan member Clarence Brandenburg addressed a small gathering of fellow Klan members in a rural Ohio field. In Brandenburg’s speech, he issued vague threats against the federal government if it continued to “suppress the white, Caucasian race.” Portions of Brandenburg’s speech had been filmed and when authorities saw it they charged him with violating “Ohio’s criminal syndicalism statute,” a policy that made it a crime to “advocate … the duty, necessity, or propriety of crime, sabotage, violence, or unlawful methods of terrorism as a means of accomplishing industrial or political reform.”

Initially convicted in court in Hamilton County, Ohio, Brandenburg was fined $1,000 and sentenced to one to ten years in prison. With the help of the American Civil Liberties Union, Brandenburg filed an appeal, claiming that his First Amendment free speech rights had been violated. The Ohio Supreme Court refused to hear his appeal so Brandenburg appealed to the US Supreme Court. In a landmark decision, the US Supreme Court sided with Brandenburg and said it was his First Amendment right to make his speech, ruling that Ohio’s criminal syndicalism statute was unconstitutional. SCOTUS articulated a new test, the “imminent lawless action” test (now known as the Brandenburg Test), to judge what was illegal seditious speech under the First Amendment.

The imminent lawless action test stated that speech could be punished only if it met two criteria: “where such advocacy is directed to inciting or producing imminent lawless action and is likely to incite or produce such action.” Therefore, speech can only be restricted if it presents a threat that is both likely to actually happen and is to happen soon. As with many Supreme Court cases involving freedom of speech, Brandenburg v. Ohio is yet another clear demonstration that speech that is repellent is just as legal as speech that is popularly approved of under the First Amendment.

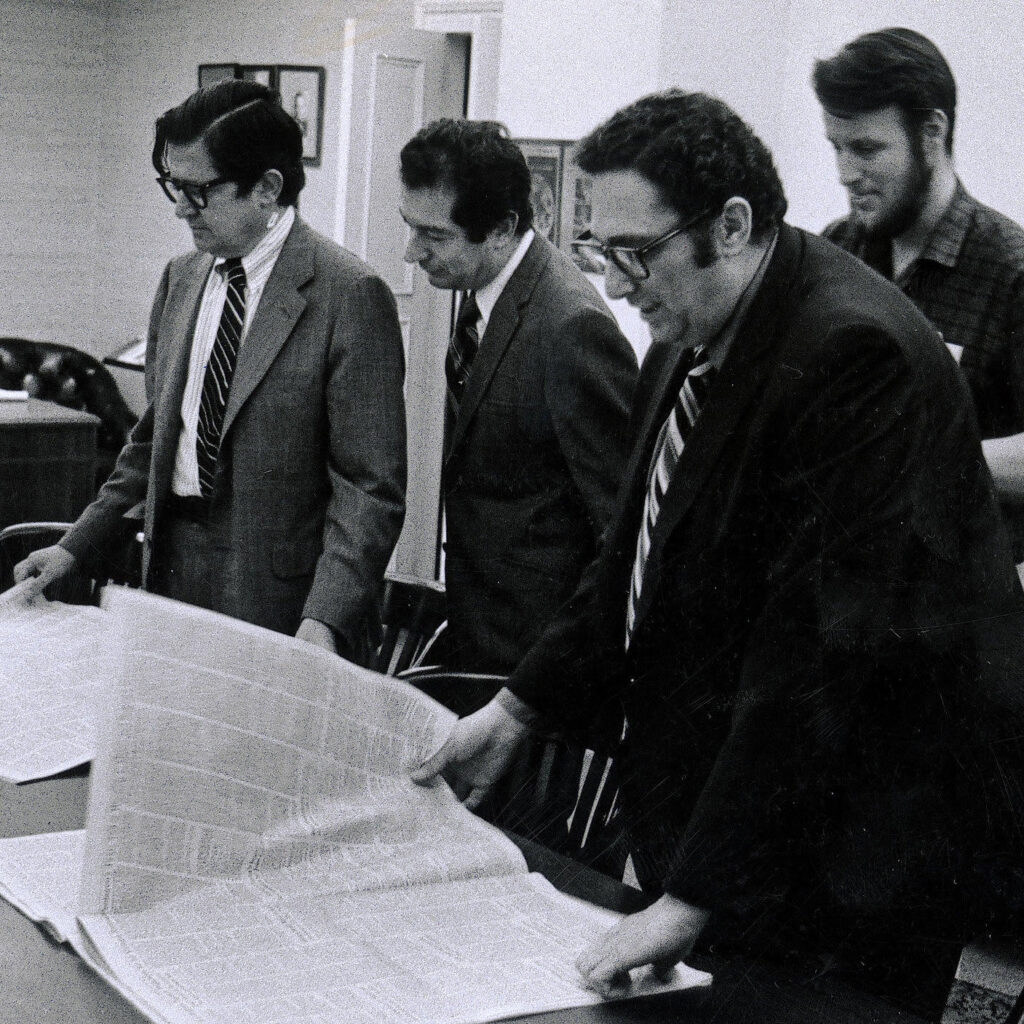

In 1968, a secret government study on America’s involvement in Vietnam was completed. The project, which comprised 47 volumes containing more than 7,000 pages, documented how presidential administrations and politicians going back to the Truman era consistently escalated America’s involvement in Vietnam. It also detailed many government secrets regarding the U.S. military’s goals, objectives, strategies, and tactics in the then-still raging conflict. The work was classified and only 15 copies were made.

In early 1971 Daniel Ellsberg, who had worked on the project, secretly made copies of the documents and passed them to reporters for the New York Times. In June of 1971, the Times began to publish the documents which they called the “Pentagon Papers.” After the Pentagon Papers were published, President Richard Nixon’s administration, citing national security concerns, filed a restraining order to halt further publication of the Papers. When an Appeals Court upheld the order, the Times made an emergency appeal to the Supreme Court, which agreed to hear the case the next day resulting in the case, New York Times v. United States.

On June 30, 1971, the Supreme Court, in a 6-3 decision, rejected the restraining order and allowed the Times to continue with publication. Justice Hugo L. Black reasoned that “only a free and unrestrained press can effectively expose deception in government.” Justice Byron R. White wrote that “in no circumstances would the First Amendment permit an injunction against publishing information about government plans or operations.” Nixon’s attempt to censor the New York Times’ freedom to publish the Pentagon Papers had been soundly defeated. The case resulted in a firestorm of outcry against government censorship and the circumstances of America’s involvement in Vietnam. The case remains one of the most important and iconic wins for freedom of speech and of the press in United States history.