![[ Obligations] Nature AND Effect OF Obligations Article 1163 – 1178](https://d20ohkaloyme4g.cloudfront.net/img/document_thumbnails/a22944c3d27ddfde5cbd95ae1fb6ca81/thumb_300_388.png)

![[ Obligations] Nature AND Effect OF Obligations Article 1163 – 1178](https://d20ohkaloyme4g.cloudfront.net/img/document_thumbnails/a22944c3d27ddfde5cbd95ae1fb6ca81/thumb_300_388.png)

Law on obligations and contracts

Law on obligations and contracts

Law on obligations and contracts

Law on obligations and contracts

Lecture notesClassifications of obligations.

(1) Primary classification of obligations under the Civil Code:

(2) Secondary classification of obligations under the Civil Code:

(3) Classification of obligations according to Sanchez Roman:

(a) Pure and conditional obligations (Arts. 1179-1192.); (b) Obligations with a period (Arts. 1193-1198.); (c) Alternative (Arts. 1199- 1205.) and facultative obligations (Art. 1206.); (d) Joint and solidary obligations (Arts. 1207-1222.); (e) Divisible and indivisible obligations (Arts. 1223-1225.); and (f) Obligations with a penal clause. (Arts. 1226-1230.)

(g) Unilateral and bilateral obligations (Arts. 1169-1191.); (h) Real and personal obligations (Arts. 1163-1168.); (i) Determinate and generic obligations (Art. 1165.); (j) Civil and natural obligations (Art. 1423.); and (k) Legal, conventional, and penal obligations. (Arts. 1157, 1159, 1161.)

(a) By their juridical quality and efficaciousness:

(b) By the parties or subject:

(c) By the object of the obligation or prestation:

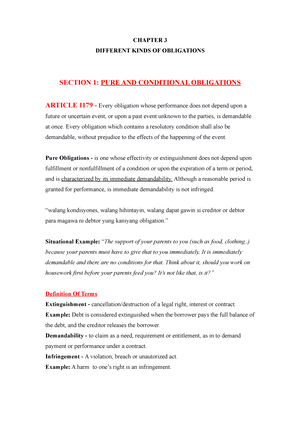

Meaning of conditional obligation.

A conditional obligation is one whose consequences are subject in one way or another to the fulfillment of a condition.

Meaning of condition.

Condition is a future and uncertain event, upon the happening of which, the effectivity or extinguishment of an obligation (or rights) subject to it depends.

Characteristics of a condition.

(1) Future and uncertain. — In order to constitute an event a condition, it is not enough that it be future; it must also be uncertain. The first paragraph of Article 1179 obviously uses the disjunctive or between “future” and “uncertain” to distinguish pure obligation from both the conditional obligation and one with a period. Be that as it may, the word “or ” should be “and.” (2) Past but unknown. — A condition may refer to a past event unknown to the parties. (infra.) If it refers to a future event, both its very occurrence and the time of such occurrence must be uncertain; otherwise, it is not a condition.

A condition must not be impossible. (see Art. 1183.)

Two principal kinds of condition.

(1) Suspensive condition (condition precedent or condition antecedent) or one the fulfillment of which will give rise to an obligation (or right). In other words, the demandability of the obligation is suspended until the happening of a future and uncertain event which constitutes the condition. (a) Actually, the birth, perfection or effectivity of the contract subject to a condition can take place only if and when the condition happens or is fulfilled. (b) It must appear that the performance of an act or the happening of an event was intended by the parties as a suspensive condition, otherwise, its non-fulfillment will not prevent the perfection of a contract. (c) There can be no rescission (see Art. 1191.) of an obligation that is still non-existent, the suspensive condition not having been fulfilled.

Distinctions between suspensive and resolutory conditions.

ARTICLE. 1181. In conditional obligations, the acquisition of rights, as well as the extinguishment or loss of those already acquired, shall depend upon the happening of the event which constitutes the condition. (1114)

Effect of happening of condition.

This article reiterates the distinction between a suspensive (or antecedent) condition and a resolutory (or subsequent) condition.

(1) Acquisition of rights. — In obligations subject to a suspensive condition, the acquisition of rights by the creditor depends upon the happening of the event which constitutes the condition.

ARTICLE. 1182. When the fulfillment of the condition depends upon the sole will of the debtor, the conditional obligation shall be void. If it depends upon chance or upon the will of a third person, the obligation shall take effect in conformity with the provisions of this Code. (1115)

Classifications of conditions.

Conditions may be classified as follows:

(1) As to effect. (a) Suspensive. — the happening of which gives rise to the obligation; and

(b) Resolutory. — the happening of which extinguishes the obligation.

(a) Express. — the condition is clearly stated; and (b) Implied. — the condition is merely inferred. (3) As to possibility.

(a) Possible. — the condition is capable of fulfi llment, legally and physically; and (b) Impossible. — the condition is not capable of fulfi llment, legally or physically.

(4) As to cause or origin.

(a) Potestative. — the condition depends upon the will of one of the contracting parties; (b) Casual. — the condition depends upon chance or upon the will of a third person; and (c) Mixed. — the condition depends partly upon chance and partly upon the will of a third person.

(a) Positive. — the condition consists in the performance of an act; and (b) Negative. — the condition consists in the omission of an act.

ARTICLE. 1183. Impossible conditions, those contrary to good customs or public policy and those prohibited by law shall annul the obligation which depends upon them. If the obligation is divisible, that part thereof which is not affected by the impossible or unlawful condition shall be valid.

The condition not to do an impossible thing shall be considered as not having been agreed upon. (1116a)

When Article 1183 applies.

Article 1183 refers to suspensive conditions. It applies only to cases where the impossibility already existed at the time the obligation was constituted. If the impossibility arises after the creation of the obligation, Article 1266 governs.

Two kinds of impossible conditions.

(1) Physically impossible conditions. — when they, in the nature of things, cannot exist or cannot be done; and

(2) Legally impossible conditions. — when they are contrary to law, morals, good customs, public order, or public policy.

Effect of impossible conditions.

(1) Conditional obligation void. — Impossible conditions annul the obligation which depends upon them. 1 Both the obligation and the condition are void. The reason behind the law is that the obligor knows his obligation cannot be fulfi lled. He has no intention to comply with his obligation.

In conditional testamentary dispositions and in simple and remuneratory donations, the rule is different. (2) Conditional obligation valid. — If the condition is negative, that is, not to do an impossible thing, it is disregarded and the obligation is rendered pure and valid. (3) Only the affected obligation void. — If the obligation is divisible, the part thereof not affected by the impossible condition shall be valid.

If no time has been fixed, the condition shall be deemed fulfilled at such time as may have probably been contemplated, bearing in mind the nature of the obligation.

Negative condition.

The above provision speaks of a negative condition that an event will not happen at a determinate time from the moment the time indicated has elapsed without the event taking place; or

(1) from the moment it has become evident that the event cannot occur, although the time indicated has not yet elapsed.

If no time is fixed, the circumstances shall be considered to determine the intention of the parties. This rule may also be applied to a positive condition.

ARTICLE. 1186. The condition shall be deemed fulfilled when the obligor voluntarily prevents its fulfillment.

Constructive fulfillment of suspensive condition.

There are three (3) requisites for the application of this article:

(1) The condition is suspensive; (2) The obligor actually prevents the fulfillment of the condition; and (3) He acts voluntarily.

The law does not require that the obligor acts with malice or fraud as long as his purpose is to prevent the fulfillment of the condition. He should not be allowed to profit from his own fault or bad faith to the prejudice of the obligee. In a reciprocal obligation like a contract of sale, both parties are mutually obligors and also obligees. (see Art. 1167.)

ARTICLE. 1187. The effects of a conditional obligation to give, once the condition has been fulfilled, shall retroact to the day of the constitution of the obligation. Nevertheless, when the obligation imposes reciprocal prestations upon the parties, the fruits and interests during the pendency of the condition shall be deemed to have been mutually compensated. If the obligation is unilateral, the debtor shall appropriate the fruits and interests received, unless from the nature and circumstances of the obligation it should be inferred that the intention of the person constituting the same was different. In obligations to do and not to do, the courts shall determine, in each case, the retroactive effect of the condition that has been complied with.

(1) In obligations to give. — An obligation to give subject to a suspensive condition becomes demandable only upon the fulfillment of the

the obligation upon the happening of the condition. Thus, he may go to court to prevent the alienation or concealment of the property of the debtor or to have his right annotated in the registry of property. The rule in paragraph one applies by analogy to obligations subject to a resolutory condition.

(2) Rights of debtor. — He is entitled to recover what he has paid by mistake prior to the happening of the suspensive condition. This right is granted to the debtor because the creditor may or may not be able to fulfill the condition imposed and hence, it is not certain that the obligation will arise. This is a case of solutio indebiti which is based on the principle that no one shall enrich himself at the expense of another. 2

ARTICLE. 1189. When the conditions have been imposed with the intention of suspending the efficacy of an obligation to give, the following rules shall be observed in case of the improvement, loss or deterioration of the thing during the pendency of the condition: (1) If the thing is lost without the fault of the debtor, the obligation shall be extinguished;

2 Art. 2159. Whoever in bad faith accepts an undue payment, shall pay legal interest if a sum of money is involved, or shall be liable for fruits received or which should have been received if the thing produces fruits.

(2) If the thing is lost through the fault of the debtor, he shall be obliged to pay damages; it is understood that the thing is lost when it perishes, or goes out of commerce, or disappears in such a way that its existence is unknown or it cannot be recovered; (3) When the thing deteriorates without the fault of the debtor, the impairment is to be borne by the creditor; (4) If it deteriorates through the fault of the debtor, the creditor may choose between the rescission of the obligation and its fulfillment, with indemnity for damages in either case; (5) If the thing is improved by its nature, or by time, the improvement shall inure to the benefit of the creditor; (6) If it is improved at the expense of the debtor, he shall have no other right than that granted to the usufructuary. (1122)

Requisites for application of Article 1189.

Article 1189 applies only if:

(1) The obligation is a real obligation; (2) The object is a specific or determinate thing; (3) The obligation is subject to a suspensive condition; (4) The condition is fulfilled; and

In case of the loss, deterioration or improvement of the thing, the provisions which, with respect to the debtor, are laid down in the preceding article shall be applied to the party who is bound to return. As for obligations to do and not to do, the provisions of the second paragraph of Article 1187 shall be observed as regards the effect of the extinguishment of the obligation. (1123)

Effects of fulfillment of resolutory condition.

(1) In obligations to give. — When the resolutory condition in an obligation to give is fulfilled, the obligation is extinguished (Art. 1181.) and the parties are obliged to return to each other what they have received under the obligation. (a) There is a return to the status quo. In other words, the effect of the fulfillment of the condition is retroactive. (b) The obligation of mutual restitution is absolute. It applies not only to the things received but also to the fruits and interests. (c) In case the thing to be returned “is legally in the possession of a third person who did not act in bad faith” (see Art. 1384, par. 2.), the remedy of the party entitled to restitution is against the other. (d) In obligations to give subject to a suspensive condition, the retroactivity admits of exceptions according to whether the obligation

is bilateral or unilateral. (see Art. 1187.) Here, there are no exceptions, whether the obligation is bilateral or unilateral. The reason for the difference is quite plain. The happening of the suspensive condition gives birth to the obligation. On the other hand, the fulfillment of the resolutory condition produces the extinguishment of the obligation as though it had never existed. (see 8 Manresa 149- 150.) The only possible exception is when the intention of the parties is otherwise. (e) If the condition is not fulfilled, the rights acquired by a party become vested.

ARTICLE. 1191. The power to rescind obligations is implied in reciprocal ones, in case one of the obligors should not comply with what is incumbent upon him. The injured party may choose between the fulfillment and the rescission 3 of the obligation, with the payment of damages in either case. He may also seek rescission, even after he has chosen fulfillment, if the latter should become impossible.

3 This remedy in case of breach of obligation should n ot be confused with rescission in Article 1281, et seq. Under the former provision, a distinction existed between rescission and resolution. (see Note under Art. 1381.)